This page gives a general introduction to the argument types in the Beta Quadrant of the Periodic Table of Arguments (PTA). It builds on a basic understanding of its theoretical framework and terminology.

The Periodic Table of Arguments analyzes an argument as consisting of three statements: a conclusion, a premise, and a lever. Each statement has a subject and a predicate. Depending on how these are arranged, an argument takes one of four argument forms. Here we discuss the beta form, where the conclusion and the premise have different subjects (a and b) and share the same predicate (X):

a is X because b is X

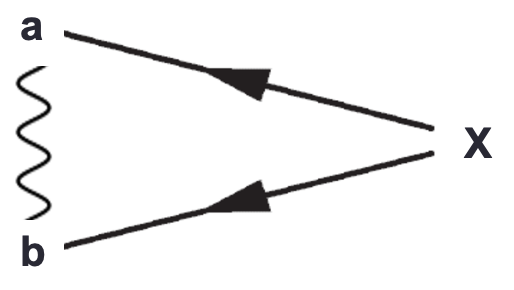

Figure 2 pictures the argument diagram of such beta arguments. The common element of the conclusion and the premise is called the fulcrum. In this case, the fulcrum is the predicate (X). The wiggly line represents the argument lever, which is defined as the relationship between the non-common elements of the conclusion and the premise. In this case, the lever is the relationship between the subjects (a and b).

Figure 2. Argument diagram of a beta form argument

The concrete lever depends in part on the argument substance. Below, we discuss the argument types with substances ss|pp|uu, ps|us|up, and sp|su|pu, respectively. The characteristics of concrete examples of the argument types can be inspected by clicking on the corresponding links.

The conclusion has the same scope as the premise

The first group of argument types in the beta quadrant is defined by having a conclusion with the same scope as the premise. Since the substance of beta form arguments is based on the tripartite typology of singular (s), particular (p), and universal statements (u), this group consists of argument types with substance ss, pp, and uu. In the literature, there are many different names for such argument types, depending on how the relationship between the subjects (a and b) is described. In the PTA, we have included the argument from analogy, the argument from similarity, the argument from comparison, the argument from equality, and the metaphorical argument.

Furthermore, we have included in this group the argument from composition and the argument from division. Here, the conclusion has the same scope as the premise in the sense that the subject of the conclusion (a) is an alternative way to describe the subject of the premise (b) (e.g., ‘the hockey team’ and ‘all individual players of the hockey team’).

Finally, this group contains the argumentum a maiore and the argumentum a minore. Here, the conclusion has the same scope as the premise, but the probability that the predicate (X) is attributed to the subject of the conclusion (a) in comparison to the probability that the predicate (X) is attributed to the subject of the premise (b) is higher or lower, respectively.

The conclusion has a broader scope than the premise

We will now look at argument types where the conclusion has a broader scope than the premise. Given the tripartite typology of singular (s), particular (p), and universal statements (u), this group consists of argument types with substance ‘ps’, ‘us’, and ‘up’. Included in this group are the argument from example and the argument from species.

The conclusion has a smaller scope than the premise

To conclude our list of argument types with a beta form, we mention the argument from totality and the argument from genus. This group consists of argument types that have substance ‘sp’, ‘su’, and ‘pu’. In other words, it includes those argument types where the scope of the conclusion is smaller than that of the premise.