Argumentation and persuasion

The argument categorization framework of the Periodic Table of Arguments (PTA) is designed to analyze argumentative or persuasive discourse, whether produced by humans or generated by machines such as LLMs. As the name indicates, such discourse contains argumentation and/or other persuasive techniques, which are analyzed in terms of specific configurations of statements put forward to establish or increase the acceptability of a central claim.

Conclusion and premise

Argumentative or persuasive discourse typically consists of a set of interconnected statements. The PTA operates on the atomic level of the discourse, describing the characteristics of each of the individual arguments contained in it. On this level, an argument is a combination of two statements. One of them is called the conclusion. This is a statement that is questioned and thus in need of support. The other is called the premise, and this is the statement providing that support. In the example below, the statement functioning as the conclusion precedes the statement functioning as the premise.

The government should not introduce a basic income. It will lead to a drop in income for most people.

The same argument can also be presented in a different order, putting the premise first and the conclusion last.

Introducing a basic income will lead to a drop in income for most people. The government should not introduce it.

Coherence markers

In practice, it may not always be immediately clear which of the two statements counts as the conclusion and which one as the premise. The arguer can diminish the chance of misinterpreting the discourse by explicitly indicating the argumentative function of the statements. This can be done by using argumentative coherence markers such as because, so, since, and therefore. The examples below contain the same argument as above.

The government should not introduce a basic income because it will lead to a drop in income for most people.

Since introducing a basic income will lead to a drop in income for most people, the government should not introduce it.

Introducing a basic income will lead to a drop in income for most people. The government should, therefore, not introduce it.

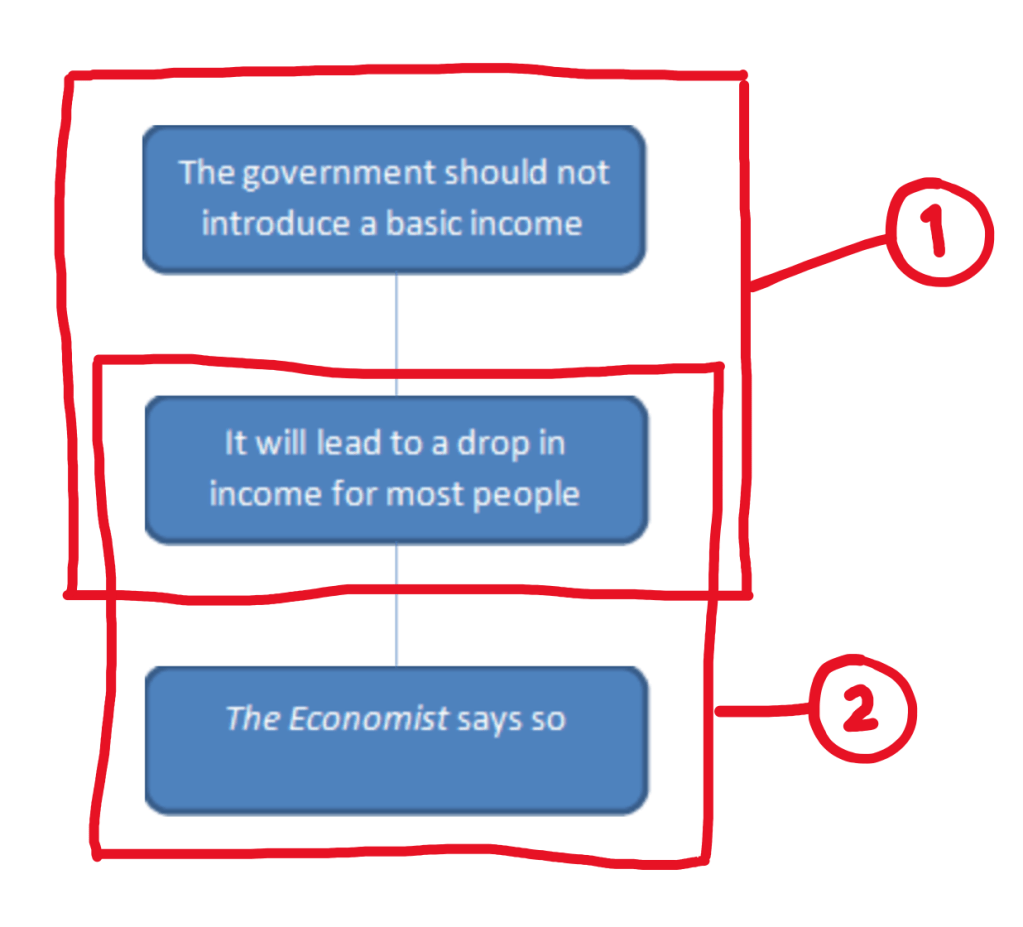

In the discourse, statements can play a double role. For instance, if a statement is supported by another statement and that statement itself is supported by yet another statement, the one in the middle functions as a premise for the first and as a conclusion for the last. An example is ‘According to The Economist, introducing a basic income will lead to a drop in income for most people. Therefore, the government should not introduce it.’ In this case, the argumentation contains two individual arguments: the first argument (indicated by 1 below) has the conclusion ‘The government should not introduce a basic income’ supported by the premise ‘It will lead to a drop in income for most people’. The latter statement also functions as the conclusion of the second argument (indicated by 2 below), where it is supported by the premise ‘The Economist says so’.

Subject and predicate

To identify the type of argument, the PTA analyzes the statements on the level of their constituents. On this sub-atomic level, each statement consists of a subject and a predicate. The subject is the entity about which something is said in the statement, and the predicate is what is said about that entity. The statement ‘The minister of education is doing a great job’, for example, has ‘the minister of education’ as its subject and ‘is doing a great job’ as its predicate.

The minister of education is doing a great job.

Argument type

The Periodic Table of Arguments (PTA) distinguishes between the types of argument based on a determination of the value of three different parameters: the form, the substance, and the lever of the argument. An argument type is simply defined as the sum of the values of these parameters. In other words, two concrete arguments belong to the same type if they match each other on all three parameters, and they belong to different types if they differ on at least one of them.

Form, substance, and lever

Various heuristics are available to determine the values of the three parameters form, substance, and lever – for an elaborate description, see How to identify an argument type? On the hermeneutics of persuasive discourse (Wagemans, 2023) or consult the Argument Type Identification Procedure (ATIP) (Wagemans, 2025).

Determining the argument form involves comparing the subjects and predicates of the two statements. For example, in some arguments, the conclusion and the premise have the same subject and different predicates, while in other arguments, it is precisely the other way around. The argument form is defined as the configuration of subjects and predicates in the conclusion and premise of the argument. For more info, please see the page on argument form.

While argument form captures the structural relationship between the premise and the conclusion, argument substance refines the classification by focusing on the semantic content of the statements involved. The way the argument substance is determined varies with the argument form. Each form has its semantic classification scheme, ensuring that the notion of substance is sensitive to the specific kinds of meaning relevant for that form. For more info, please see the page on argument substance.

Finally, the argument lever is a description of how the premise and conclusion of an argument are connected. Different from purely formal types of connections, such as a major premise or a conditional, the value of the lever depends not only on the argument form but also on its substance. Establishing the values of these two parameters restricts the search space for finding the lever. For more info, please see the page on argument lever.