This page gives a general introduction to the argument types in the Alpha Quadrant of the Periodic Table of Arguments (PTA). It builds on a basic understanding of its theoretical framework and terminology.

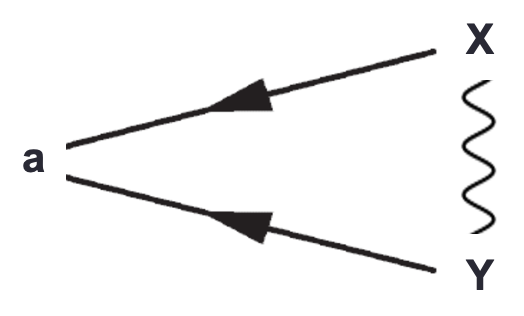

The Periodic Table of Arguments analyzes an argument as consisting of three statements: a conclusion, a premise, and a lever. Each statement has a subject and a predicate. Depending on how these are arranged, an argument takes one of four argument forms. Here we discuss the alpha form, where the conclusion and the premise share the same subject (a) and have different predicates (X and Y):

a is X because a is Y

Figure 1 pictures the argument diagram of such alpha form arguments. The common element of the conclusion and the premise is called the fulcrum. In this case, the fulcrum is the subject (a). The wiggly line represents the argument lever, which is defined as the relationship between the non-common elements of the conclusion and the premise. In abstract terms, then, the lever of an alpha form argument is the relationship between the predicates (X and Y).

Figure 1. Argument diagram of an alpha form argument

The concrete lever depends in part on the argument substance. Below, we discuss the argument types with substances FF, VF, VV, PF, and PV, respectively. The characteristics of concrete examples of the argument types can be inspected by clicking on the corresponding links.

Statement of fact (F) as a conclusion

Conclusions containing a statement of fact (F) are often supported by premises also containing a statement of fact (F). This means that the lever expresses a connection between two factual predicates. In its simplest form, the predicate of the premise (Y) is a sign of the predicate of the conclusion (X). In the literature, an argument based on such a symptomatic relationship is classified as an argument from sign (Sig).

Facts can also be connected by a causal relationship, which can be used in two directions: from the presence of the cause, it can be inferred that the effect is present. This is called an argument from cause (Ca). And from the presence of the effect, it can be inferred that the cause is present, which is called the argument from effect (Ef).

If a known or unknown cause produces various effects, then these effects are correlated. When one such effect is used in an argument to support the presence of another effect, it is called an argument from correlation (Cor). Finally, the PTA distinguishes the argument from motive (Mot), where a prediction about behaviour, which also counts as a statement of fact, is supported by another statement of fact that functions as a motive for this behavior.

Statement of value (V) as a conclusion

We will now examine alpha form arguments with a statement of value (V) as their conclusion. Such a conclusion is often supported by a premise containing a statement of fact (F) or a statement of value (V).

When a conclusion that expresses a statement of value (V) is supported by a premise that expresses a statement of fact (F), the lever is a relation between a fact and a value. Examples of such argument types are the argument from criterion (Cr), where the fact functions as a criterion that justifies the attribution of the value, the argument from definition (Def), where it functions as its definition, and the argument from subsumption (Su), where it can be subsumed under the heading of the value expressed in the conclusion.

When a conclusion that expresses a statement of value (V) is supported by a premise that also expresses a statement of value (V), the lever is a connection between values. The PTA distinguishes several of these relations, which are at the basis of the argument from norm (Nor), the argument from instantiation (Ins), and the argument from disqualifier (Dis).

Statement of policy (P) as a conclusion

To conclude our list of argument types with an alpha form, we mention the pragmatic argument (Pra), the argument from principle (Pri), the argument from evaluation (Ev), the deontic argument (Deo), and the teleologic argument (Tel). All these argument types have a statement of policy (P) as their conclusion. The difference is that in a pragmatic argument, the conclusion is supported by a statement of fact (F), in an argument from principle and from evaluation, by a statement of value (V), and in a deontic and teleologic argument, by another statement of policy (P).